Welcome, trivia-seekers, to the eighth issue of the Curiosity Catalogue.

Before I begin with this week’s essay, though, I just wanted to say that I hope you’re safe, and doing as well as can be. It’s been a hellish week in India, with WhatsApp, Twitter and human kindness substituting for a public healthcare system. The case load shoots up, and every day, it feels like COVID takes over more of our lives and sanity. I thank my stars - no one in my house has fallen sick, and my parents and grandmother are either partially or fully vaccinated now.

Still, even within this bubble of privilege, it’s been a depressing few days. Part of me didn’t want to write this issue, because it felt a little pointless. In the end, it became a way for me to stop doom-scrolling, and made me feel like I had a semblance of control over things.

I really hope wherever you’re reading this, it brightens your day just a little, as a reminder that outside this catastrophe, there’s weird trivia to be discovered, and a world to be fascinated by.

About a year ago, when the pandemic began (this is the last time I mention it, I promise), I came across a rather interesting mask-making tutorial. The video itself was unremarkable - what caught my eye was the brand that put it out. You can see for yourself below.

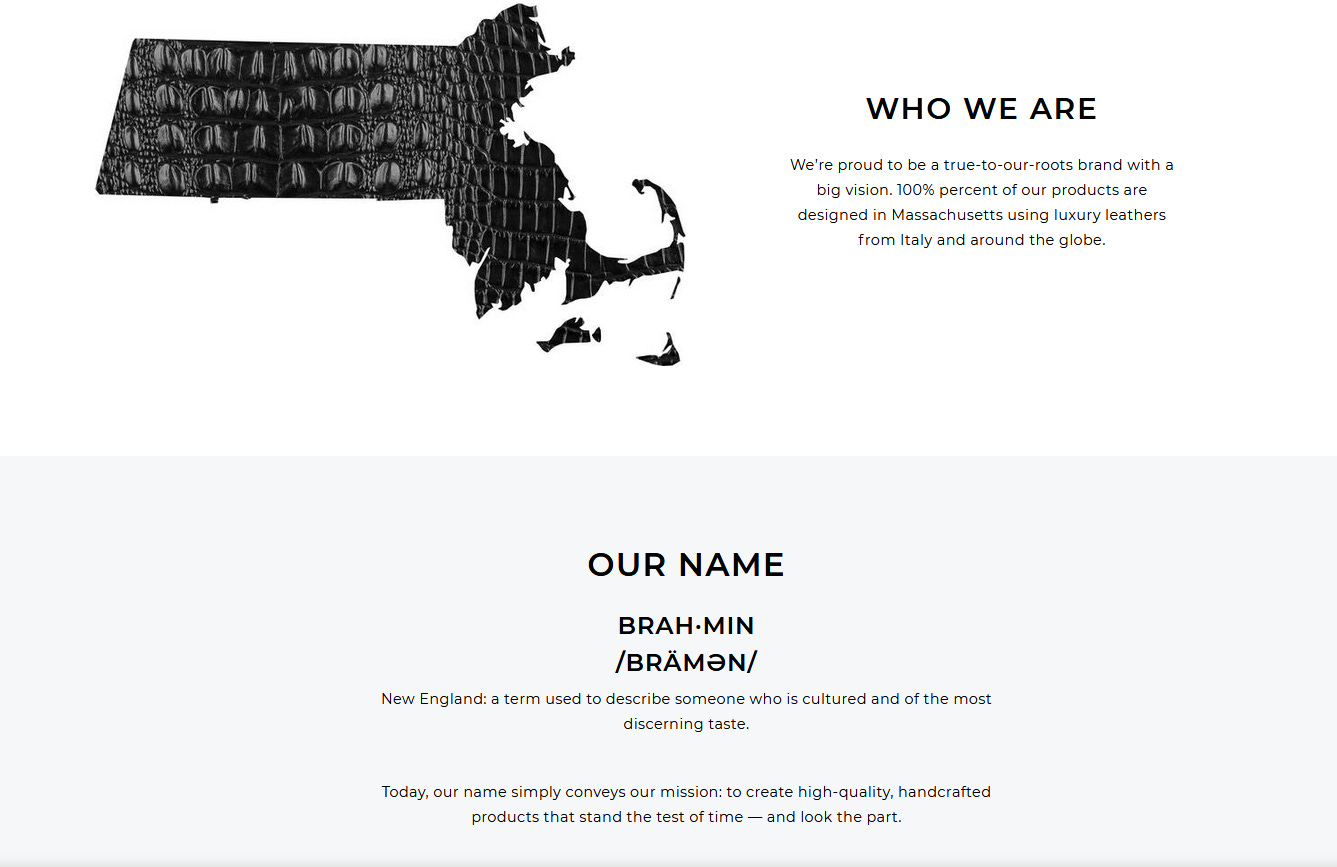

Mind you, this wasn’t an Indian brand that called itself Brahmin, it was an American one (they’re a luxury handbag maker). And that’s partly why I came across it at all - friends on Instagram were criticising the brand for their ignorance of the name’s connotations in India.

Though the ignorance was undeniable, I had a feeling there was more than just cultural appropriation gone way, way wrong here. The name rang a bell - I vaguely remembered coming across the term ‘Boston Brahmins’ in Bill Bryson’s Made in America (though I haven’t been able to locate the reference while researching for this issue) and wondered whether it was related to this.

As it turns out, it very much was.

A writer named Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr was the first to use term ‘Boston Brahmins.’ He wrote a piece called ‘The Brahmin Caste of New England’, published in The Atlantic Monthly (now known just as The Atlantic) in 1860. It isn’t available on the Atlantic’s online archives, but became part of later book by Holmes called Elsie Venner, available in full on Google Books.

It’s no secret where Holmes got the term from, or what he meant by it. He was celebrating his belief in the superiority of his ilk - the rich, white, old families that were amongst the earliest settlers in New England, that part of the USA’s east coast comprising the states of Maine, Vermont, New Hampshire, Massachusetts, Connecticut and Rhode Island.

With an immense sense of entitlement, he differentiated the ‘harmless, inoffensive, untitled aristocracy’ that constituted the Brahmin intellectual elite from the ‘country-(folk) whose race had been bred to bodily labour.’ The Boston Brahmins, he said

“[were] merely the richer part of the community, that live in the tallest houses, drive real carriages…, kid-glove their hands, and French-bonnet their ladies’ heads, giver parties where the people who call them by the above title are not invited, and have a provokingly easy way of dressing, walking, talking, and nodding to people, as if they felt entirely at home, and would not be embarrassed in the least, if they met the Governor, or even the President of the United States, face to face.

…

It has grown to be a caste, - not in any odious sense - but, the repetition of the same influences, generation after generation, it has acquired a distinct organisation and physiognomy, which not to recognise would be mere stupidity…

This east coast aristocracy, in his eyes, was born to lead (quite literally, given their lineage), and had a penchant for intellectual pursuit (but hey, he said there was nothing odious about it, so I guess it’s okay).

It’s true, members of these families have been and still are at the helm of government, industry and academia. Wikipedia has a long list of these families and their notable descendants, and some of them are recognisable even to me, like T. S. Eliot, John Adams and Franklin Roosevelt. Their roots in Boston have tied them closely to Harvard and other Ivy League Universities over generations. All of this is entirely unsurprising, as well, with their privilege.

While they considered themselves a class (and caste) apart, most had little knowledge of the civilisation whose terminology they’d borrowed while naming themselves. Some thinkers from this group, though, caught up in the intellectual currents of the time, became founders of and subscribers to transcendentalism, a philosophical thought inspired partly by Hinduism. Transcendentalists were disillusioned with the world as they saw it. Ralph Waldo Emerson, of a Brahmin lineage himself, referred to the society around him as a ‘mass’ of ‘bugs or spawn.’ They sought refuge in nature and the divine, and in this search found guidance in Hindu thought. Henry David Thoreau, Emerson’s protege, wrote the following of his experiences at Walden Pond:

“In the morning I bathe my intellect in the stupendous and cosmogonal philosophy of the Bhagvat Geeta, since whose composition years of the gods have elapsed, and in comparison with which our modern world and its literature seem puny and trivial; and I doubt if that philosophy is not to be referred to a previous state of existence, so remote is its sublimity from our conceptions. I lay down the book and go to my well for water, and lo! there I meet the servant of the Bramin, priest of Brahma and Vishnu and Indra, who still sits in his temple on the Ganges reading the Vedas, or dwells at the root of a tree with his crust and water jug. I meet his servant come to draw water for his master, and our buckets as it were grate together in the same well. The pure Walden water is mingled with the sacred water of the Ganges.”

This appreciation of Hinduism that was in the air manifested in interesting ways - a ship initially commissioned in the US Navy, which fought in the Civil War, was called the USS Varuna, named after the Vedic God. (Decades later, there would also be a USS Indra and USS Krishna).

In general, the pursuit of divinity seems to have been the exception, and not the norm, amongst the self-proclaimed Brahmin elite. For most, the term was little more than a signifier of superiority.

160-ish years on from Holmes’ essay, the legacy of the Boston Brahmins lives on. The term Brahmin itself is used in the city to connote a sort of old-money elegance. Remnants of this distinct Anglo-Saxon culture, a friend who studies in Boston tells me, are still visible outside the more cosmopolitan parts of the city. Nowhere is this more apparent than the Brahmin brand (based near Boston, in case you were wondering) that inspired this essay - just look at the screenshot of its website below.

The Boston Magazine certainly fancies the term, using it as shorthand when reviewing places around town. Like in the screenshot below, where it awarded the Best Breakfast to the Ritz Cafe in 1983

Some seem to be tiring of this antiquated culture, though not for the reasons one might hope. When describing changing trends in interior design for the magazine, Rachel Slade wrote in 2012, “For generations, if you wanted others to know you’d made it in this town, you decorated in the stuffy Brahmin style. Not anymore.”

My personal favourite mention of the term in the magazine, though, is actually from a review of a restaurant called Brahmin, for no reason other than that one of the reviewers favourite dishes was beef short ribs. At least there’s some irony to appreciate.

The Round-up

Though I didn’t find Holmes’ essay in the Atlantic’s online archive, reading through the list or articles from this era was quite surreal. I’d recommend you peruse through some of the pieces up there, like the then editor’s endorsement of Abraham Lincoln in the 1860 elections, or a review of the ‘recently released’ On the Origin of Species by a certain Charles Darwin. We’ve all been craving for the world before COVID - here’s a rather unorthodox way to visit it.

If you’re tired of everything going on around us and want an escape from the world of humans, you should watch My Octopus Teacher, a new documentary on Netflix. It’s a simple, feel-good story with stunning visuals and starring a friendly octopus. What’s not to like?

About me: I'm Shantanu Kishwar, a lover of fun trivia and well-made hummus. I currently work as a Teaching Assistant at FLAME University, Pune. Feel free to follow my sporadic updates on Twitter and Instagram.

I hope you liked this issue. If you’re new here and want the next straight in your inbox, subscribe above. Feel free to reply with thoughts, recommendations and suggestions. Do share this with other curious people you know. I’d really appreciate it, and hope they will as well.