#07: Family histories

The story behind an old family photo; and four sisters who fought a dictator

Issue 7 | 10th April, 2021

Hello, inquisitive people of the world, and welcome to the seventh issue of the Curiosity Catalogue.

For me, this is the most special issue yet. For the first time ever, I’ll be publishing someone else’s writing. Kartika Menon, a dear friend and fellow history-buff, delves into her family’s past, and tells a tale of her ancestral home.

After this story from South India, we move to South America, and the story of a very different family. Particularly, a family of sisters, and their martyrdom at the hands of their country’s dictator.

Tales from a Tharavadu

by Kartika Menon

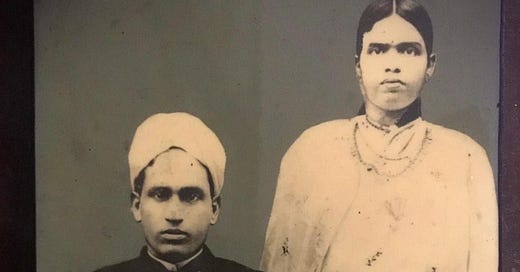

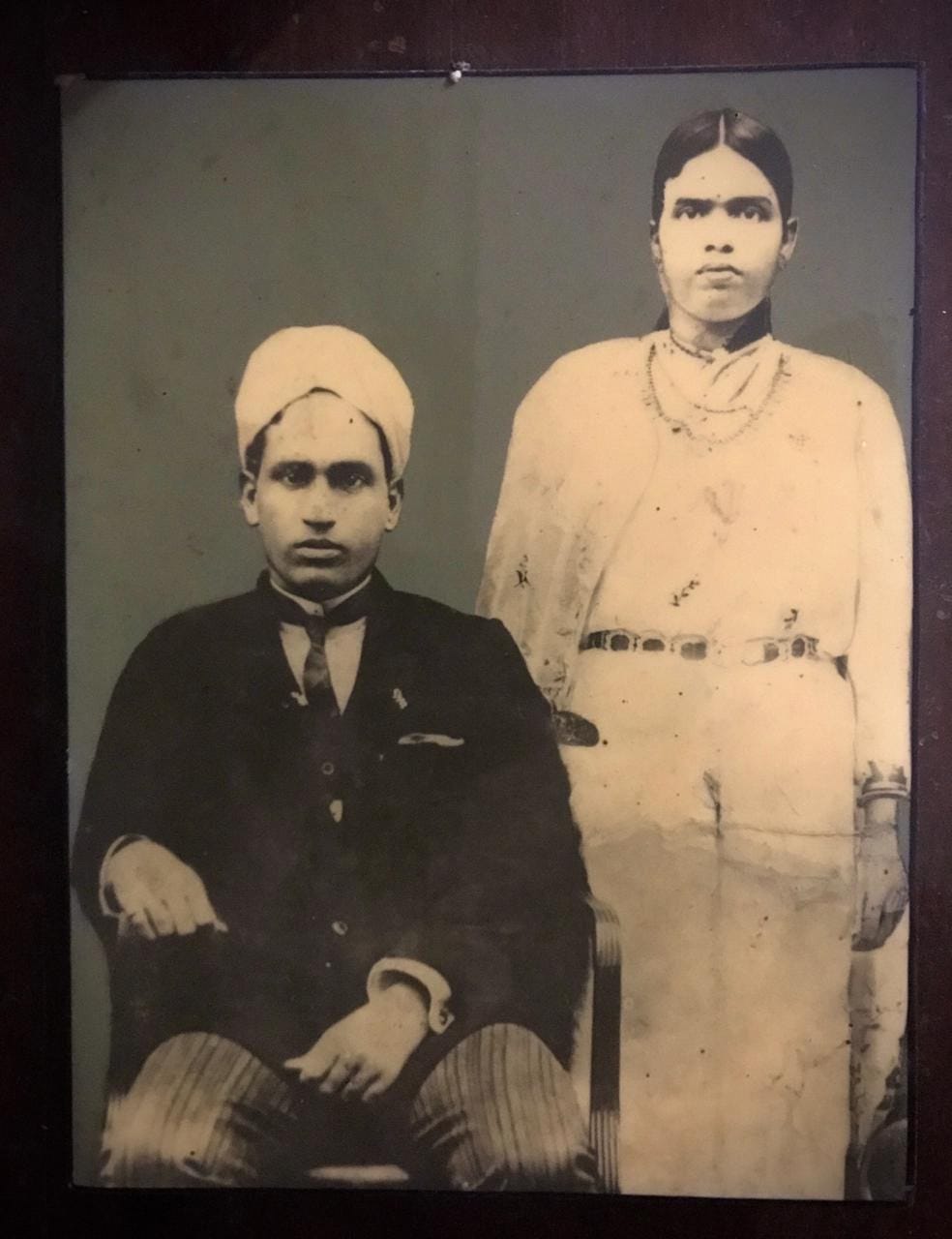

In the port town of Beypore in Kozhikode lies my ancestral house, a Nair tharavadu, ‘Kizhekkepattu Puthukudi’. Hanging on a wall there is this photo of my great great grandparents, Ramakuruppu and his wife, Kunjulakshmi Amma. In typical British-Indian fashion, he wears a suit and turban. She wears a traditional odiyanam, a gold waistband. It’s a photo taken soon after their wedding, some time in the 1910s. No one's sure of the exact date.

At this time, the Puthukudi tharavadu was a traditional ‘ettukattu’, an eight-block structure. A typical tharavadu is a ‘naalukettu’ or a house with four blocks, but larger or wealthier families could afford an ettukattu, or a ‘padinaarukettu’, with sixteen blocks. Each set of four blocks surrounded a courtyard, known as a ‘nadumittam’. These houses were built of teak, had gabled windows for ventilation, and were covered by the sloping tile-roof seen even today in many Kerala homes.

The central temple of our tharavadu was dedicated to the goddess Bhadrakali. Sacred spaces for the snake deities were included within the compound - the nagarajavu and the nagakanniga. There was a ‘kolam’, a traditional bathing area for the family. Large coconut plantations and mango orchards surrounded the house, tilled by labourers of marginalised communities who were tied to the land. A rigid and exploitative caste hierarchy allowed for the upkeep of these fields for several decades.

The dawn of the twentieth century was a period of flux for traditional Nair practices. Nair families typically traced their descent through matrilineal succession, a system known as marumakkathayam. Within this form of kinship, consanguineous marriages were common, where the woman is married to her father’s sister’s son. This form was seen as proper, because it was outside the line of matrilineal succession.

There were many attempts to regulate such practices through colonial legislation. Despite the formal abolition of matriliny in 1933, however, many families, including mine, still trace their ancestry through the maternal side. Legally, I have adopted my father’s surname, but traditionally, it is my mother’s tharavadu that I belong to. I am the youngest of the clan, “and maybe the last”, says my great uncle, “so write down this history before it is forgotten”.

Here it is, then - what I have gathered about my great great grandparents:

Ramakurappu studied at St Aloysius College in Mangalore, now Mangaluru, passed his District Pleader’s Examination and began practice as a vakil in Pattambi, in Palakkad. He later shifted his practice to Ponnani, the little Mecca of Malabar, where his practice flourished, and he was known as an expert at cross-examination. So revered was his practice, says my great-uncle, that when he walked the streets, people would stand to pay their respect. He used to frequent the local club, playing table tennis for hours, and striking up a conversation with every passer-by. He was never to be found without his pocket-watch, or his chellam - a brass box which stored his special preparation of tobacco with jaggery. (On a few occasions, his eldest grandson filched some of that tobacco, and had a better time than he was meant to.)

Ramakuruppu’s wife, Kunjulakshmi, meanwhile, suffered from chronic epilepsy. After a debilitating stroke, she spent her last years recuperating at Puthukudi. The two had many children, but only my great grandmother, Saudamini, and her elder sister, Sarojini, survived. Their other siblings died tragic and sudden deaths when they were very young. Kunjulakshmi herself passed away soon after giving birth to Saudamini, and so, little is known about her life.

Ramakuruppu went on to practice till the age of eighty, and then settled down at Puthukudi. It was at the tharavadu that Ramakuruppu’s daughter Saudamini was married to Achutha Menon. The marriage proposal came through Achutha’s father, who used to frequent Ramakuruppu’s practice at Ponnani.

Saudamini and Achutha Menon had seven children, of which five survive today. Four sons, and one daughter. My great uncles, Ramachandran, Shankaran, Achuthan, and Ashok; and my grandmother, Shantha, through whom the lineage is carried on. She says she was her grandfather’s favourite. She remembers sitting on his lap, him reading to her from the Ramayana and Mahabharata, and when spirituality wasn’t the flavour of the day, they turned to Tarzan panels in the Indian Express.

My grandmother married her first cousin, Balasubramaniam, and the pair lived at Puthukudi for several years. By this time, however, the once-large estate had been partitioned many times, sold to different buyers, and the house itself renovated to look more ‘modern’. As cultural changes swept across the state, many traditional homes were changed and rebuilt. So, the gabled windows, the roofs, and the nadumittam all disappeared. Although, the kolam still exists, some distance away from the main house, green and overgrown with algae.

Growing up, I spent many summers at the tharavadu, as the whole family got together for the annual pooja. It was an elaborate affair, involving days of preparation. All the cousins would sit together to pluck and sort the chethi poovu, the red ixora flowers used as offering. We would slit coconut leaves to hang around the temple complex, reveling in the clean swipes of the curved knife. As the sun set, we would place lamps all around the complex, stepping on fallen frangipani flowers as we walked around with an oil can in one hand, and cotton in the other. We would then sit outside the main shrine for hours on end while the namboodiri priest conducted the pooja.

From these evenings, my memory brings me flickers of white light, the buzzing of fat insects, and the background hum of my family chanting hymns. It brings me heat, rolling beads of sweat, and a general stickiness in the air. Mostly, though, it brings me the smell of hot payasam in uralis, large brass vessels waiting to be emptied with a relish. Once the pooja was over, and all the chores complete, the cousins would gather in the main hall for our own special ritual - choreographing dances to the latest Bollywood songs. No Beypore pooja was complete until we had subjected the whole family to our impressive range of embarrassing moves.

In all those years, I never once looked closely at the photos on the wall. Today, looking at this one, I am glad I know more about my great great grandfather, but I wonder about the woman next to him. Who was she, really? What was she like? She looks a lot like my grandmother - something in the way she stands, and her defiant stare. I wish there were more answers. In a world where information is so easily accessible, it is a novel yet frustrating experience to be told there is simply no way to find out.

As the years go by, reunions are harder. My grandparents no longer live at Puthukudi, and the cousins are scattered across the world. Visits are shorter, summers are hotter, and there’s never enough time. So much has changed, but isn’t that how it works? The tharavadu, though empty on most days, still stands. The temple is tended to, and a pooja is held regularly. We attend, if not in person, then virtually. Payasam is served at home, not in an urali but in a glass bowl. Bollywood has consistently disappointed this decade when it comes to family appropriate dance numbers, but at my eldest cousin’s wedding a year ago, we all danced to the 90s hit Ajooba, pleased to find our repertoire of awkward steps still intact.

History and memory, inextricably linked, twist and morph, but survive in unexpected ways. They’re kept and found in old photographs, century-old ornaments, the clanging of the temple bell, and most importantly, in the stories - many forgotten, but replaced with new ones that will be told and retold as the world moves ahead.

The Butterflies who brought down a dictator

I came across the story of the Mirabal sisters almost by accident. Searching through the shelves of a small bookshop in Dharamkot in 2017, I found a used copy of Julia Alvarez’s In the Time of the Butterflies. With my small travel-budget already stretched, it was about all I could afford (the hawkish look of the lady at the counter drained me of my courage to walk out empty-handed).

As is the fate of most fiction I purchase, this gathered dust in my bookshelf for years. I finally found my way to it last month, and so it was that I learned the story of these sisters who basically said, '“f*** it, we’re overthrowing this dictator.”

In the mid-20th century, citizens of the Dominican Republic lived a repressed life under the military dictatorship of Rafael Trujillo. Trujillo, known popularly as “El Jefe” (the boss) or “El Chivo” (the goat), brought some material prosperity to the nation through his iron-fisted rule. This prosperity came at a cost, naturally. Civil liberties were lost, political competition quashed, and dissenters persecuted. He also took control of key industries, and at the time of his death “he controlled nearly 80 percent of the country’s industrial production,” according to historian Frank Moya Pons.

There was resistance to his rule, no doubt. An underground movement emerged domestically, supported by exiles from abroad. Though led primarily by men, in the legacy of this resistance the memory of the Mirabal sisters stands prominent.

The four sisters - Patria, Minerva, Dede and Maria-Teresa - were born to a decently wealthy family. Their lives of comfort didn’t lend themselves to radical politics. Encounters with revolutionary youth and a good education in early adulthood brought with it a sense of disillusionment. All but Dede joined the cause. The sisters became known as “la Mariposas” or “the Butterflies” (hence the title of Alvarez’s book). They gained popularity amongst their fellow revolutionaries, and notereity amongst government officials.

In the late 1950s, in the face of global condemnation and increasing domestic opposition, Trujillo became desperate to quash dissent. He set his sights on the symbolic power of the Butterflies, and ordered their assassination in 1960. The three sisters (Dede stayed away from these matters) were ambushed after a visit to their jailed husbands (also revolutionaries) and killed. Attempts to pass it off as a car accident were recognised for the lies they were. Resentment against the regime grew, and karmic retribution struck Trujillo just months later. In 1961, he was ambushed and assassinated while in his car.

Alvarez’s novel took the the story of la Mariposas to the world, though she maintains that hers is entirely a fictional account that attempts to capture the spirit and not the facts of their life. The UN recognised their bravery, declaring the anniversary of their assasination the International Day for the Elimination of Violence Against Women.

Their story made its way to the screen in 2001, in a movie by the same name starring Selma Hayek. It’s available on YouTube, and linked below.

The Round-up

Kartika’s foray into her family’s past reminded me of Manu Pillai’s book The Ivory Throne, where he tells the tale of the last Queen of the Travancore Kingdom, Sethu Lakshmibai. If the essay has piqued your interest in the state’s history, you might enjoy that as well. There are a also few pieces on Kerala’s history in his collection titled The Courtesan, the Mahatma and the Italian Brahmin.

I’ve recently been enjoying Where the Rain is Born, a collection of poems, short stories, essays and travel writing on Kerala, edited by Anita Nair. It has both original writing in English as well as translations from Malayalam, with pieces by the likes of Arundhati Roy, Jeet Thayil, Kamala Das and Shashi Tharoor.

The Dominican Republic has a rich and complicated history. It’s unwittingly been a key part of modern history, having been the first place that Christopher Columbus actually settled when he reached the New World (though he of course thought he’d reached India). Even after freedom from European colonialism, though, it spent large parts of the early 20th century as a ‘banana republic’ exploited by American fruit companies. You can read more about that here.

In the Time of the Butterflies isn’t the only novel to have been inspired by Trujillo’s reign; Nobel Prize winner Mario Vargos Llosa’s Feast of the Goat similarly explores Trujillo’s tyranny. While Time of the Butterflies was about the decades of Trujillo’s reign, though, Feast instead focuses on the end of his rule, the conspiracies that brought him down, and the chaos of these uncertain times.

Despite it’s tumultuous history, it’s fared far better than its neighbouring country on the island of Hispanola, Haiti. Vox’s Borders website, and the video below, explain why.

About me: I'm Shantanu Kishwar, a lover of fun trivia and well-made hummus. I currently work as a Teaching Assistant at FLAME University, Pune. Feel free to follow my sporadic updates on Twitter and Instagram.

I hope you liked this issue. If you’re new here and want the next straight in your inbox, subscribe above. Feel free to reply with thoughts, recommendations and suggestions. Do share this with other curious people you know. I’d really appreciate it, and hope they will as well.

A note: While the newsletter is free, and always will be, I’ve added Amazon affiliate links to products I discuss or recommend. If you choose to buy, say, a book I mention with this link, I earn a very small commission. The newsletter takes many hours to research and write, and this helps keep it going. Feel free of course, to give your local bookshop a call instead, it would make me just as happy.